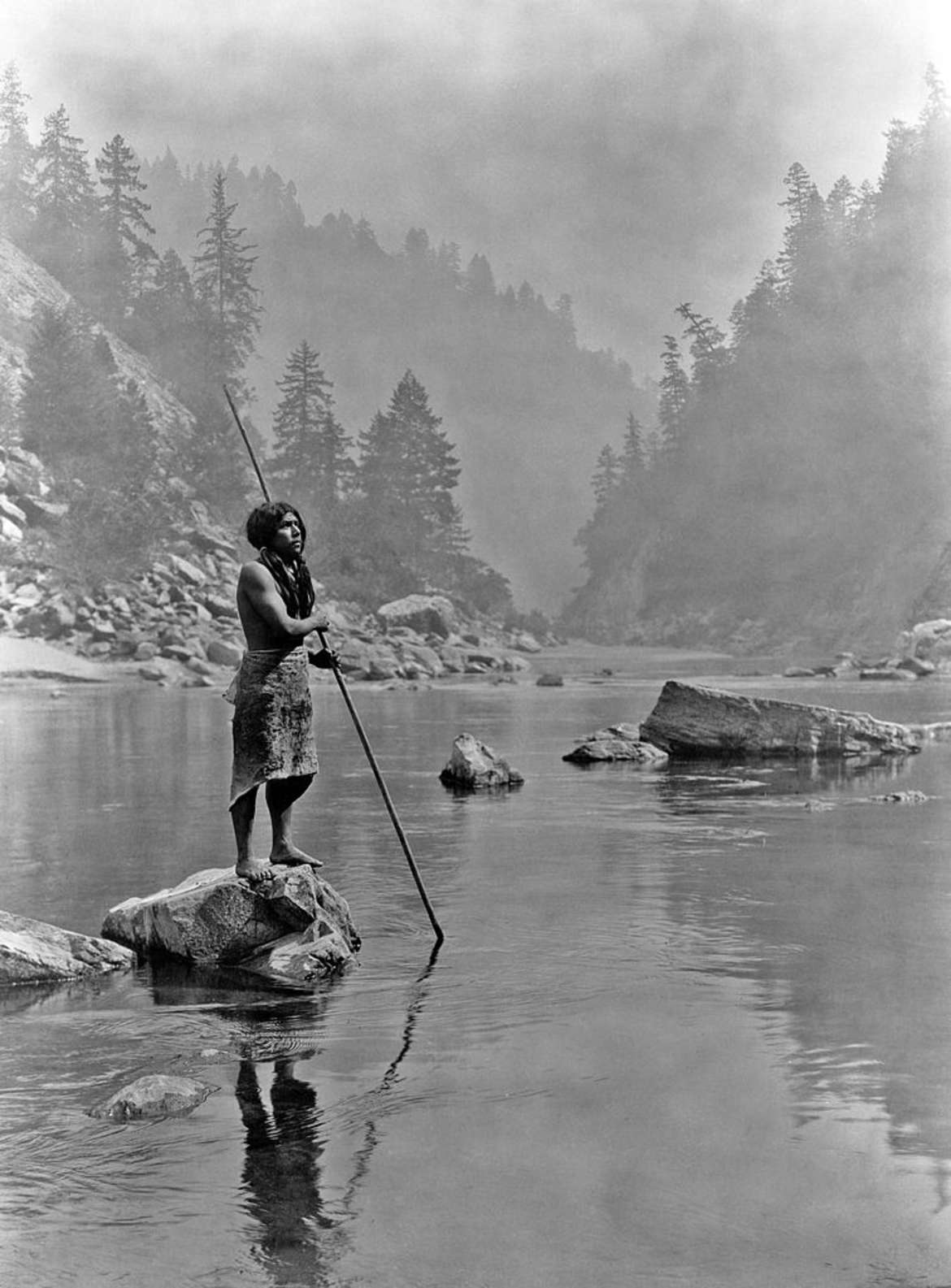

How the western idea of the wild and conservation insurance policies have affected tribal peoples

The grasslands of America’s Nice Plains stretch for miles throughout the sagebrush steppe of South Dakota so far as the Black Hills. It was right here, in 1980, that acres of spruce timber and creek-carved canyons had been declared a ‘wilderness’ reserve by the U.S. authorities.

To the Indigenous North American Indians, nonetheless, the world was not wild; nor was it a ‘wilderness’. ‘We didn’t consider the good open plains, the gorgeous rolling hills, the winding streams with tangled progress as ’wild’,’ mentioned Luther Standing Bear of the Oglala Lakota Sioux individuals. ‘To us it was tame. Solely to the white man was nature a wilderness.’ In just a few phrases, Luther Standing Bear had articulated two very totally different approaches to the pure world.

The idea of ‘wilderness’ has lengthy existed, in Western tradition, as a spot of pristine pure magnificence — unpolluted by human life: an Eden sanctuary, an antidote to city residing. Through the nineteenth century such concepts had been mirrored in artwork of the time. ‘In wilderness is the preservation of the world,’ wrote Henry Thoreau. For naturalist John Muir, communion with nature served to clean his spirit ‘clear’, whereas the photographer Ansel Adams’ images of Yosemite nationwide park famously contained no signal of human life.

In attributing other-worldly qualities to nature, nonetheless, and in seeing them as sacred areas the place God lives however man should not, concepts developed which had been arguably on the root of conservation insurance policies. ‘For many years, the thought of ’wilderness’ has been a basic tenet of the environmental motion,’ wrote the historian William Cronon. Such insurance policies adversely affected the Indigenous tribal peoples for whom such ‘wild’ locations had been merely ‘residence’.

It was in Yosemite that the world’s first nationwide park, which had been cared for by the Ahwahneechee individuals for generations, was established. Yellowstone Nationwide Park was subsequently created in 1872, when the federal government evicted the Indian tribes who’re thought to have lived there for greater than 11,000 years.

At the moment there are an estimated 120,000 protected areas worldwide, masking practically 15% of the world’s land floor. Conservation is undoubtedly very important when the organic variety of the planet is so threatened. However the sorry backdrop to those statistics — the story that’s neglected within the need to protect the ‘wild’ — is certainly one of intense human struggling. For within the creation of reserves, hundreds of thousands of individuals — most of them tribal — have been evicted from their properties.

In India, a whole bunch of 1000’s of individuals have already been displaced from parks within the identify of conservation, whereas in Africa mass evictions from protected areas have taken place, together with the Batwa ‘pygmies’, who had been forcibly moved from Uganda’s Bwindi Forest so as to shield the mountain gorillas and the Waliangulu individuals of Kenya, who as soon as lived within the Tsavo Park space. ‘This variant of land theft is quickly rising as one of many largest issues confronting Indigenous peoples at the moment,’ says Stephen Corry of Survival Worldwide.

For tribal peoples, it issues little whether or not the theft of their homelands has been for conservation or business causes. Dispossessing Indigenous homeowners for conservation might seem extra benign, however for tribal peoples the results are equally catastrophic. As soon as separated from their lands, tribal peoples start to lose the traditions, abilities and data that collectively weave the tapestry of id; thus follows a profound lower in psychological and bodily well being.

Lands are equally ‘divorced’ from the Indigenous homeowners. 80% of the world’s biologically wealthy areas are the territories of tribal communities who, for millennia, have discovered ingenious methods of catering for his or her wants and sustaining the ecological steadiness of their environment. Such sustainable ideas are evident within the well being of the Amazon: a lot of the rainforest that lies outdoors tribal reserves has been denuded, whereas inside Indigenous areas it largely stays intact. Equally, the one remaining rainforest on the Andaman Islands is discovered throughout the Jarawa peoples’ reserve. It’s usually exactly as a result of ‘wild’ locations have been taken care of by their Indigenous guardians that they’ve been chosen by conservationists as reserves.

Pondering has undoubtedly moved on because the days of Yosemite and attitudes have modified even since 1964, when the US Wilderness Act said that, ‘a wilderness is hereby acknowledged as an space the place man himself is a customer who doesn’t stay.’ The adoption of the U.N.‘s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007 said that tribal peoples want to provide their ’free, prior and knowledgeable consent previous to the approval of any mission affecting their lands.’

However there’s nonetheless a protracted technique to go. Tribal peoples proceed to be unnoticed of discussions regarding the safety of their homelands, although so usually it has been they who, within the phrases of Davi Kopenawa, ‘protect the flood plains, the hunt, the fish and the fruits.’ Corry thinks that the conservation of biodiversity ought to solely be promoted with the consent of the Indigenous. ‘Defending ecosystems doesn’t imply defending them from the individuals who have all the time been their guardians,’ he says. ‘Conservation rights shouldn’t trump tribal rights.’

There may additionally be room for a broader cultural goal; one which lies in reshaping the favored thought of ‘wilderness’ in western pondering, by acknowledging the traditional interrelationship of man and the pure world. For harmful attitudes are born partly of dualistic concepts; in emphasizing the separateness of man and nature. ‘Any manner of nature that encourages us to imagine we’re separate from it’s more likely to reinforce irresponsible behaviour,’ says William Cronon. The world’s tribal peoples nonetheless intuitively grasp this symbiotic relationship higher than most; within the phrases of Davi Kopenawa, ‘The setting isn’t separate from ourselves; we’re inside it and it’s inside us.’