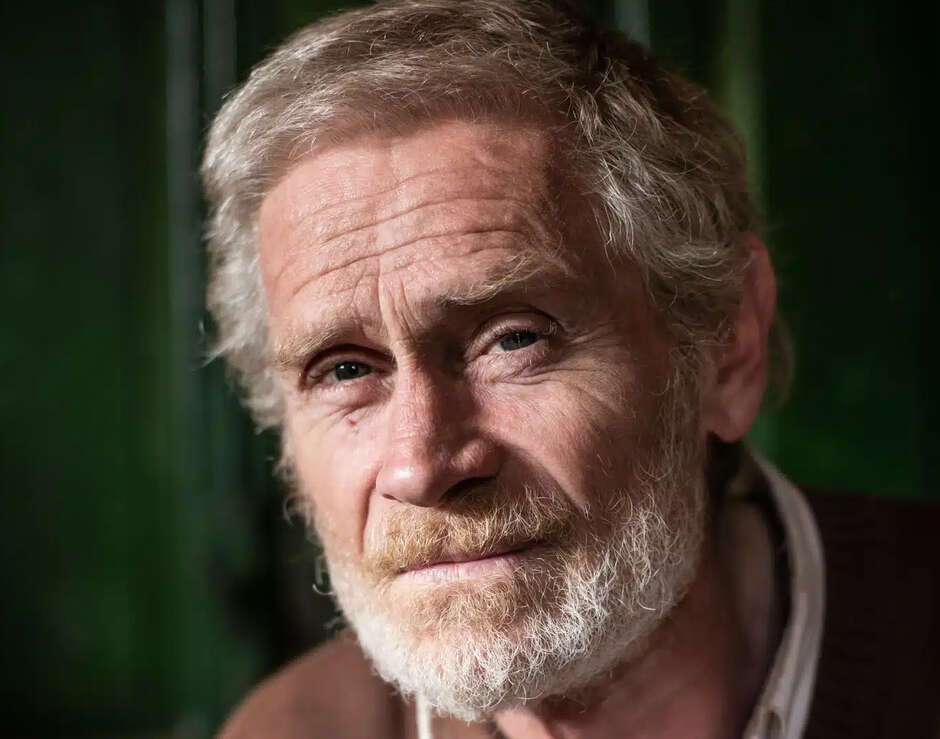

Our outdated good friend John Palmer died not too long ago in Argentina. He had a lifetime’s dedication to the Wichí folks and in his absolute dedication to working alongside them within the defence of their rights, he was the very mannequin of what a recent anthropologist who works with Indigenous peoples ought to aspire to be. That is our tribute. An edited model of this obituary was printed in The Guardian.

The lifetime of the anthropologist John Palmer, who has died aged 69, was ceaselessly modified when he first met the Indigenous Wichí folks of South America’s Gran Chaco area.

John was educating English in Argentina as a niche yr pupil in 1974, after a childhood in Devon. It’s arduous to think about a larger distinction between south-west England and the dry, dusty, scorchingly sizzling Chaco, however within the Wichí – who’re so softly-spoken their dialog is extra like whispering – John encountered folks whose qualities he massively admired.

He returned to the Wichí in 1978-9 for 2 years of doctoral fieldwork, residing within the tiny group of Hoktek T’oi (‘Stunted Lapacho Tree’). It was to be his religious dwelling ever after.

As soon as again within the UK, John struggled to reconcile the huge gulf in values and outlook between the Wichí and Nineteen Eighties Britain. Holed up in a flat in Oxford, he eked out a residing as a part-time proofreader for OUP, whereas making an attempt to wrestle the complexities of Wichí philosophy right into a coherent thesis, below the unforgiving eye of his doctoral supervisor. (His thesis was ultimately printed in Spanish in 2005, entitled ‘Wichí goodwill: an indigenous spirituality.”)

However the Wichí had not forgotten him, and in 1990 they wrote to Survival, requesting that funds be raised to assist him return, to help them within the preparation of a land rights declare. Twenty-seven communities alongside the Pilcomayo River had banded collectively, wanting to say communal land title to 500,000 hectares of their ancestral land – a tiny portion of their unique territory, however an enormous, unprecedented declare by Argentinian requirements.

John’s return to the Wichí marked the beginning of the remainder of his life, and after that he hardly ever got here again to the UK. Working within the harshest conceivable circumstances, John and some colleagues ready an in depth land declare report.

At its coronary heart was a singular map dotted with a whole bunch of toponyms – names marking a spot of geographical or social significance, or the place one thing humorous or tragic had occurred way back. This intimate data of each nook of their land was irrefutable proof that the Wichí’s occupation of the world stretched again deep into the previous.

The land declare was submitted in 1991, and began its tortuous journey by way of Argentinian paperwork and the courts, within the face of bitter opposition from the settlers who now occupied massive components of Wichí land, and their highly effective political allies.

John quickly turned his consideration to the Wichí communities he knew finest – these alongside the Itiyuro River, resembling Hoktek T’oi. Along with his help they began their very own political group, which they known as Zlakatahyi (‘Our River’), and started to say their rights, even because the rampant and unlawful deforestation of their territory continued round them.

It’s arduous to think about somebody whose outward look was much less suited to standing as much as the soya barons and politicians who’d conspired to rob the Wichí of their land. However beneath the light, courteous and reasonably old style manner, John had a stubbornness and dedication which weren’t simply deflected, and he thought one ought to stand as much as bullies.

In 2009 his work acquired some recognition from his friends within the anthropological group with the awarding of the Royal Anthropological Institute’s Lucy Mair Medal. By now he’d additionally secured a part-time educating place at Salta College.

Late in life John married Tojweya, a Wichí lady, they usually went on to have six kids. In 2012 Argentinian film-maker Ulises Rosell made a documentary, The Ethnographer, on John and Tojweya’s life collectively, and John’s indefatigable exertions to help the Wichí within the face of a steady onslaught towards their lives and values.

John and Tojweya’s household represented the approaching collectively of two very completely different worlds, a stark distinction to the literal bulldozing of Wichí land and tradition by the dominant settler society. John was probably the most unworldly of characters, totally tired of materials issues, and with a really deep moral sense. His integrity, decency and humour made a powerful impression on those that bought to know him, and he had a loyal group of family and friends who supported him and his work financially for many years, figuring out that in any other case he would very probably starve.

His premature demise is a big loss not solely to his household and the Wichí, however to all that had been fortunate sufficient to know him. He’s survived by Tojweya and their kids, his brother Man and his sisters Julia and Sarah, and has been buried in Hoktek T’oi.